Conversation Print Top 'Quilt of the Month'

Published: Saturday, 19th December 2009 09:44 AM

The Conversation Print Top

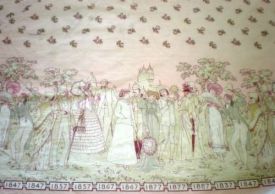

When a quilt has no known provenance it can be difficult, perhaps impossible, to piece together its whole history. This is the case with the Conversation Print Top, donated to the Quilt Museum and Gallery in 2005. Who made it? Why and exactly when? These questions may never be fully answered but deciphering the individual fabrics that make up this finished piece is a fascinating process in itself. Technically not a quilt, for it has never been padded and sewn onto a back piece, the Conversation Print Top consists of a hand-sewn hexagonal-pieced centre of conversation prints and a Walter Crane - designed border print machined to the centre. Made from multi-coloured cotton, its overall colour impression is pink and having been kept in storage, it is in very good condition.

The Border

Walter Crane (1845-1915) was a leading figure in the Arts and Crafts Movement and best known for illustrating children's books. He also designed textiles, ceramics, wallpapers and stained glass. The Conversation Print Top border is a depiction of fashion between 1837-1887 and it seems likely that this fabric was printed in celebration of Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee in 1887. Each couple on the border is roughly placed above two dates representing a decade and starting in the year of Queen Victoria's accession to the throne in 1837.

The female figure above 1837-47 wears a simple white muslin gown, looking unencumbered by stays and petticoats, popular from 1800 to the early Victorian period. The male figure for this decade wears the simple but exquisitely tailored style made so famous by Beau Brummelin the early part of this century. Paradoxically defined as a dandy, Beau Brummel's style was in fact based on very masculine aesthetic principles where form and proportion were designed to be accentuated.

The 1847-57 female figure is drawn standing sideways to display her large shawl, a popular garment at this time. She also wears a poke bonnet that covers her fashionable ringlets. Skirts were gradually starting to increase in size around this period and by the 1850's, whalebone hoops reduced the need for extra petticoats and the lighter and more flexible steel hoop was introduced. These crinolines were at first domed in shape and looked very similar to a beehive, as shown in the 1857-67 female figure and a shape echoed in the domed structure behind this couple.

The 1867-77 couple wears simpler-looking garments suitable for outdoor sporting pursuits. Here, the male figure is carrying a hunting gun and the female's jacket and skirt appear less restrictive than the preceding crinoline.

A significant transition of style can be seen in the aesthetic couple for 1877. Curiously, these two figures are not allotted a time frame of one decade but appear solely above the year 1877. The Aesthetic Movement reached its height between 1870-1880 and so perhaps this couple represents the very pinnacle of this decorative style of fashion. The Aesthetes, including writers, artists and designers such as William Morris and Walter Crane, were influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite paintings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones. These artists idealized medieval style and envisioned a more authentic freedom and naturalness in their art. Hence, on the Conversation Print Top, the female figure is wearing a gown that accentuates her natural form and is tied simply at the waist. Her hair falls loosely, unadorned by hat or bonnet, and she is carrying a fan that appears to be made of feathers.

The peacock feather was a predominant Aesthetic motif as was the sunflower, carried here by the male figure, and the favourite flower of perhaps the most famous of male aesthetes, Oscar Wilde. Representing the sun and happiness because of its shape and colour, the sunflower head turns with the movement of the sun. This motif therefore also came to represent loyalty or slavish adoration and was often ridiculed by Punch cartoonists in reaction to people's growing and seemingly insatiable desire to decorate themselves and their homes in the current aesthetic taste.

The aesthetic couple on the Conversation Print Top certainly appears to represent such adoration. The male figure is wearing typical aesthetic dress of jacket and breeches, which were often made of velvet, and is gazing at his bashful companion against a romantically picturesque backdrop of a gothic-style castle. The stiff formality of the last couple, representing 1877-87, contrasts sharply with the preceding aesthetic style. Again drawn from the side as in the female figure for 1847-57, here the intention is to display the large bustle on the back of the skirt. The bustle eventually reached its biggest size in 1885 before dying out in 1887.

Located above this fashion frieze is a repeat pattern of rose buds in the same delicate pink and green of the overall design and similar to the floral design of the flower held by the female figure for 1857-67. Flower buds, and the rose in particular, are one of the most popular floral motifs suggesting youth and new beginnings. Significantly, the year 1887 was not only Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee but also the year in which the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society was formed with Walter Crane as President. The Society's purpose was to promote the exhibition of decorative arts and its first exhibition was held in 1888. Perhaps the rosebud design on the Conversation Print Top border therefore represents not only a symbol of new beginnings for the 1857-67 couple but also for the continuing artistic vision of designers such as Walter Crane.

The Patchwork Centre

The centre of the Conversation Print Top is made up of hexagonal pieces consisting of floral prints as well as 'conversation' prints, also known as 'craft' or 'novelty' prints. The centre's predominant colour theme is black, blue and red on a white background - the main colours used in conversational prints. The various flower designs are known as 'neats' because they were simple floral or geometric motifs repeated as a regular, often symmetrical, pattern. These were inexpensive to produce and therefore extremely popular in the second half of the nineteenth century. The floral prints were probably produced in the same way as conversation prints, that is, as mill engravings. A mill engraving is a print made with copper rollers upon which was engraved a design transferred from a steel roller called a 'mill'. It was a technique used for small-scale and detailed designs and a close inspection of the conversation prints in the centre of this Top piece reveals an extraordinary amount of detailed motifs.

A conversation print is one that depicts a real object or creature (excluding flowers because they belong to their own motif family) and is often whimsical, humorous or just strange. Cheap to produce, they became very popular in the last quarter of the nineteenth century and designers continuously searched for variety and 'novelty' for their patterns. Today, many of these designs have lost their context and are consequently difficult to identify. For example, one design on the Print Top is that of a mouse or rat crouched on an egg. Perhaps this was a humorous depiction of a household pest raiding a larder. Other examples on the Print Top (although not all are analysed in this article) include:

Animals such as dog faces, a cat with a guitar, a running hare and a decoratively-bridled horses head. The horse perhaps represents a mode of transport while the hare could denote sporting pleasure, here hunting. Cats and dogs, but especially cats, were a novelty theme in late nineteenth century designs because more of these animals were being kept as pets by newly prosperous Victorian households. Objects such as umbrellas, decorative vases, padlocks and horseshoes. Almost any object could be designed and, if it proved popular, would be reprinted. These objects found on the Print Top are functional and would have easily related to everyday contemporary life. Sports themes such as the rowers on the Print Top became more popular in the early twentieth century with a bigger growth in the leisure industry but can be found occasionally on late nineteenth century prints. Circus motifs were more popular in the late nineteenth century, especially for children's fabrics. One example seen on the Print Top is an athletic-looking trapeze artist.

Games were also a popular motif and the Print Top shows various designs relating to cards and dominoes. On one design, a monkey is sitting astride a card, the six of hearts, waving what may be a flag. In contrast to these leisure pastimes the reality of work is also depicted on the Print Top. Tools such as rakes, forks and spades recall the work of a farm labourer, a design printed at a time when, ironically, cheap factory labour was threatening the very existence of traditional farming communities.

Indeed, the conversation prints on the Print Top, themselves factory produced, cheap to manufacture and of generally poor quality, were the very kind of product that designers such as Walter Crane and William Morris reacted against. The Arts and Crafts Movement embraced the highest standard of design and quality of materials as well as sumptuous use of colour. In turn, their own designs became increasingly unaffordable for the majority of consumers. The history of the Conversation Print Top brings forward ideas relating to both ends of the late nineteenth century design spectrum - Walter Crane's vision of hand-crafted beauty and the mass production of cheaper, functional fabrics. Along with the history of Victorian fashion depicted in the Print Top's border and the wide variety of motifs in the pieced centre, the Conversation Print Top can certainly claim valid historic importance within the Quilt Museum and Gallery's collection.

By Anna Honing, Museum Volunteer

Conversation Print Top

Conversation Print Top

1837-1847 Couple

1837-1847 Couple

Arts and Crafts Couple

Arts and Crafts Couple

The Patchwork Centre

The Patchwork Centre

Conversation Print Object Motifs

Conversation Print Object Motifs

Conversation Print Card Motifs

Conversation Print Card Motifs